|

Philip Sutton died unexpectedly on 12 June 2022. Philip's Climate Emergency framework provided the grounding for CACE, the council climate emergency movement, and climate emergency more broadly. _______________________________________________________________________________________________ Since his sudden death on 12 June, much has been written about Philip Sutton, the visionary thinker behind the “climate emergency declaration”. Philip’s prolific lifetime of work is captured in this Guardian obituary. Since the 1970s, Philip has published two seminal climate books, authored environmental legislation still in use, drafted legislation that the climate movement should be lobbying governments on, and shaped the climate conversation globally. Philip was not a climate scientist but he grilled climate scientists to reveal the assumptions and realities behind often opaque scientific statements. Philip worked long hours every single day at the theoretical “coalface” of climate thinking. Below the grassroots, down the end of a long tunnel - far from light, air, recognition, financial support. The work’s urgency was his drive; the urgency for a future for his kids and all vulnerable populations and ecosystems. Anyone that recognised Philip’s brilliance is wondering how we carry on his legacy. Philip’s consolidated climate thinking on Climate Rescue is perfectly summarised in this November 2021 interview. Philip’s immediate thinking preceding his death is summarised in this email to the Victorian Climate Action Network. A group that was to work on his current Climate Rescue project is continuing that work. Philip was always decades ahead of the “mainstream” climate movement, which has recognised and used some of his thinking but not the more difficult aspects. It is inevitable that we will have to engage with the these more difficult aspects if we decide to have a future. This blogpost aims to capture the aspects of Philip’s core thinking that has not been widely understood or embraced by climate movements. It is a call for climate movements to understand and rally around Philip’s thinking in the quest to restore a safe climate. The grief that many are feeling to lose this brilliant, big-hearted, deep thinker must be harnessed to implement what is likely the only path that will save us. A pathway that Philip envisaged over a decade ago. How we restore a safe climate Twenty years ago, when NGOs such as Greenpeace were campaigning on cuts of 60% emissions, Philip and a couple of others (Adrian Whitehead and Matt Wright) were looking at zero emissions. Not net-zero emissions still talked about today but true zero or a near zero emissions society achieved at emergency speed. Philip’s thinking can be summarised by what we need to achieve for a viable future. The fundamentals have not altered in more than a decade and are increasingly validated by IPCC and other bodies as they catch up:

The key here is that the only safe position is to reverse global warming and restore a safe climate (i.e. safe greenhouse gas concentrations and whatever else it takes). Without the combined three actions (zero, drawdown, cooling), we risk tipping into runaway climate change or Hothouse Earth, from which there is no conceivable return. The idea that we can stop warming at an arbitrary point and stay there is conjecture. Targets such as “zero by 2050” are political, not scientific; and suicidal based any analysis of the science. And these three actions are required to occur at emergency speed. Philip was at pains to emphasise that acting at emergency speed requires:

Elements of Philip’s thinking that got “mainstream” legs include

Philip’s (and David Spratt’s) thinking is succinctly captured in this Breakthrough paper, Climate Emergency Explored. Elements of Philip’s thinking that have been adopted by the leading edge of the climate movement are:

Two of Philip’s central ideas have have not gained traction with the leading edge or broader climate movement but are absolutely central to avoiding global climate catastrophe and restoring a safe climate are:

Mobilisation and Cooling the planet are discussed in more detail in sections below. Emergency declaration + mobilisation only work hand in hand Declaration and mobilisation go hand in hand - with mobilisation the ultimate goal and declarations just a mechanism for mobilisation. For example:

Philip outlined what a national Climate Emergency and Mobilisation Act would look like. It involved a lot of government restructuring and goal setting to prioritise the work needed to reverse global warming. Philip emphasised the appropriate steps for target setting:

Policy makers and mainstream Environmental NGOs (ENGOs) prefer to set targets based on what they think is “realistic” with a few tweaks to business as usual. This is suicidal when winning slowly means losing. In 2013 Philip, working with a team that included Adrian Whitehead and Tiffany Harris, developed a plan for what mobilisation could look like at the local government level. This work later became core material that underpins the work of CACE (Council and community Action in the Climate Emergency). Mobilisation is hard; local governments simply do not have the budget to achieve all that needs to be done. State governments and federal governments with their big economic and regulatory levers are the levels of government that could truly implement an emergency response, but state and federal governments in 2016 weren’t anywhere near declaring a climate emergency let alone mobilising. That’s why the Climate Emergency Declaration campaign was focused on local government. As far back as 2008 in this ABC interview with Robyn Williams and in his seminal 2008 book with David Spratt, Climate Code Red, Philip talked about going down to any level of governance - down to the household or individual if required, for traction on mobilisation. Declaration + mobilisation is inconvenient. It cannot exist in a neoliberal frame, which prioritises infinite growth and the welfare of corporations. Mobilisation is a green-new deal, hard targets and working out what we do to meet those targets. It also means regulation to stop bad things, not just economic signals to slowly phase them out. Central governments need to wrest back power from decades of neoliberalism to make mobilisation happen. On the idea of “economic signals”, Philip recently did a back-of-the-envelope calculation for a carbon tax that would get us to zero in under ten years. He estimated the tax would need to be around $300 a tonne - up a bit from the “ambitious” $50 we might hear. As Philip then said, “a $300 carbon tax would lead to chaos”. While a tax might have a role in subsets of activity, we need central planning to guide this kind of massive infrastructure work. Cooling the planet Point three of the pathway to restoring a safe climate, cooling the plant, is perhaps the most misunderstood. Geoengineering as a whole is frowned upon by many people keen on saving the planet primarily because it is seen as an “out” for fossil fuels - that they might use it as a reason to keep emitting. Needless to say, we need to campaign for both “negative emissions” and cooling the planet at emergency speed. The term geoengineering represents a broad range of options to cool the planet but Philip usually only referred to solar radiation management (increased albedo to reflect the sun) for cooling the planet, as in general solar radiation management represents a much lower risk option to create a global cooling than some of the options more broadly defined under the term geoengineering (eg BECCs). Solar radiation management includes relatively low-tech options such as painting roofs white or highly reflective roads, to more complex options as reflecting sunlight back out into space by enhancing cloud formation, or maintain (reflective) levels of sulphur dioxide in our atmosphere as we progressively shut down coal power plants. To reject the imperative of solar radiation management or alternatives outright is to not understand the inconvenient reality that at “equilibrium”, we have already reached around 2.5C of warming and built in 25 metres of sea level rise; most of this warming has not yet manifested in average surface temperatures due to:

As such, zero emissions alone, if achieved today, would very likely not save us. Zero emissions alone is a narrative hangover from decades ago. It persists in climate circles. Zero emissions alone ignores the numerous feedback loops we have tripped that are speeding up warming, the 1C of cooling we are currently engineering, and the global lag in realised surface temperature. If we care enough about people, populations, ecosystems, the web of life, a future for ourselves and our kids, we will take radical action to cool the planet. Any action should aim to minimise negative side effects; however, we’ve left it too long to imagine we come out of this unscathed. We need to go with the lesser of many evils. Climate campaigns coming together? Can the climate movement get behind Philip’s framework to restore a safe climate? In a call for them to lead, the role of E-NGOs has to be highlighted here. There is a strong case that the large E-NGOs (yes, all of them) have held back progress as they clung to the idea that telling the truth wasn’t good business and campaigning for incremental action was the best way to get outcomes. E-NGOs vehemently fought “emergency”, the E-word, until grassroots campaigns - starting in Darebin Vic, got the ball rolling with the initial climate emergency declaration in 2016. There were tears, including Philip’s, among campaigners that had lobbied Darebin council when that first climate emergency motion passed in December 2016. (Special mention here to other Darebin campaigners, such as Adrian Whitehead for campaigning the council on a climate emergency declaration, Jane Moreton and her booklet that went global Don’t Mention the Emergency?, Margaret Hender and Mik Aidt for their work on the Climate Emergency Declaration platform.) When the large ENGOs finally noticed the emergency campaign had gone global, by about 2019, after it spread like wildfire through the UK councils, they raced to catch up to the bandwagon. Once they’d wrested the reins from grassroots campaigners, the large E-NGOs steered the wagon away from the trackless unknown of what a climate emergency declaration and mobilisation entails back onto the sealed road of feelgood rhetoric and incremental change. Targets were watered down, the idea of mobilisation vanished and the declaration plus a few council actions was the outcome. Councils that had declared were looking at each other for guidance on how to mobilise. Some of them had a bit of a go and CACE provided a framework for that mobilisation. While there was resulting innovation that has influenced higher levels of government, none wanted to go too far out on a limb. This Breakthrough paper is a survey of what declared Australian councils had progressed around February 2020 with regard to climate emergency imperatives, and a 2022 Australian survey by Cedamia. Since 2019, the rise of Extinction Rebellion, Greta Thunberg and Fridays for Future (School Strikes) mean that grassroots are again visibly leading. However, ENGOs have become intertwined with School Strikes around the world. XR’s demands are:

Last word Most governments will take the easiest path available so campaigners need to be laser sharp and unanimous in their messaging if they want a meaningful outcome. Rather than campaigning for what we think governments will tolerate we need to campaign for what actually needs to be done, ie we need to campaign to reverse global warming and restore a safe climate. Philip was optimistic that saving the planet was still feasible if we adhered to emergency speed to negative emissions (zero plus drawdown) and cooling the planet, underpinned by declaration plus mobilisation. Can we rally around Philip’s core thinking to save ourselves?

0 Comments

by Bryony Edwards / CACE "Since this blog was originally posted the Victorian Government passed a new version of the local government act which now explicitly requires councils to act on global warming. Section 9.2c now states "the economic, social and environmental sustainability of the municipal district, including mitigation and planning for climate change risks, is to be promoted". You can find the new Victorian Local Government Legislations here."

Advice to councils on climate risk has been on the same trajectory for years now - ignorance is no excuse and can only increase your exposure. Indeed, councils are complaining they bear the burden of too much risk with minimal resources. Many council associations are pushing for higher levels of government to take more responsibility for climate risk and provide clear demarcation lines for where council responsibility starts and ends. The current state of this legal and financial framework is captured well in a recent webinar (February 2020) delivered by Sarah Barker, the Global Head of Climate Risk Governance at international law firm Minter Ellison). The examples used were from Australia and internationally and were focused on infrastructure and planning issues. The first port of call for a homeowner whose insurance claim is refused is usually the council, eg, Why hasn’t council done more to prevent the flooding? Why was construction allowed in a floodplain? Why didn’t council warn me about the risk? Barker’s message for all councils is: 'There’s a financial and legal imperative to act and act now - across all [council] business, every decision that’s made. Ask how robust are the assumptions that we use in planning and how do we stress test against the plausible range of climate futures...sticking your head in the sand is no longer passable’. Using modelling based on historical records rather than future scenarios counts as sticking one’s head in the sand. Force Majeure or ‘Acts of God’ don’t work with insurance companies as the frequency of acts of global warming rapidly grows. And assessing risk means accommodating for the worst case scenarios. Avoiding litigation risk is key but Barker also provides examples of financial benefits for councils that properly assess and respond to climate change risk, including cheaper finance from new ‘sustainable’ loan products and lower insurance premiums and broader coverage for the council and the community. The Commonwealth Bank of Australia’s recent risk analysis of their mortgage portfolio is highlighted by Barker. The Bank looked at five categories of risk in a 5x5 meter square grid across Australia. The five risks tested were bushfire, increasing windsheer, coastal inundation and freshwater flooding, and drying soil, which turned out to be the most significant risk for the bank, because drying soil messes with housing foundations, and drying soil can and is resulting from changing climate conditions. So what are some concrete examples of what councils can do to avoid litigation and improve insurance and loan rates? Bushfire - Planning restrictions; rehydrating landscapes using Sponge city strategies and increasing soil water; planting fire-retardant trees as breaks; consider the merit of new estates abutting bush or plantations. Increasing windsheer - Pushing for a higher standard of construction in wind prone areas. Coastal inundation - Purchasing at-risk properties and using them for dune building; revegetation and wetland restoration to reduce the impact of storm surges; preventing building from occurring in the first place; tidal walls, advocating up for state and federal action. Freshwater flooding - Sponge city strategies; more porous surfaces; capturing excess such as in domestic water tanks, facilitating more moist and thus more absorbent soils; water sensitive urban design. Drying soils - Sponge city strategies and appropriate regional strategies should help to alleviate and reverse this drying. Aside from planning and infrastructure, how would council risk manifest in other portfolio areas such as waste and more broadly, community welfare? This probably remains to be seen; however, where neighbourhoods with no canopy cover are 10 degrees celsius higher than leafy suburbs nearby it’s not hard to imagine the litigation that might occur following a heatwave. It’s worth also pointing out that all of Barker’s examples of risk exposure involve the resilience of the council community with regard to global warming, as opposed to councils’ political responsibility to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. It is a lucky coincidence that many strategies that build council resilience to global warming also reduce emissions. This includes across green space, stationary energy, waste, and roads. For example, planting trees helps mitigate extreme heat and sequester carbon dioxide; entering a large power purchase agreement for renewable power with other councils lowers power costs and reduces stationary energy emissions. And Barker’s message to councils that pass motions to acknowledge the climate emergency is that: ‘You can’t just declare an emergency and not change the way things happen. You need a credible and reasonable approach to starting that journey. The declaration is a good way to signal to insurance companies that you take it seriously, but councils have to follow up.’ Where can councils go for risk management resources? Barker pointed to the Task Force on Climate Related Financial Disclosures as well as the Bureau of Meteorology and CSIRO. Naturally, the council doesn’t need to go it alone and can join with other councils for economies of scale. Will councils be able to implement the sweeping changes that minimise exposure if they have not prioritised responding to climate risk? The answer is likely no. The change in how councils work and prioritise their work is so sweeping that these changes would not likely happen if competing with other priorities, and we have already seen this play out to some degree. As far as we know, no council has prioritised their climate emergency response as their number one priority after delivering their core services. What would an emergency response by a council actually look like? CACE has developed a recommendation for a staged implementation for a climate emergency response on our website. In short, it boils down to the following:

TODAY IS MORE THAN A NEW YEAR - IT WILL NEED TO BE THE BEGINNING OF A NEW ERA IN CLIMATE CAMPAIGNING12/1/2020 By Philip Sutton Today is the first day of 2020 and I think 2019 needs to be the last year of a thirty year era of climate campaigning and action. Across the country fires are raging, with a scale and intensity that confirms that Australia and the world is now living in the early stages of truly catastrophic climate change. Climate disaster has become a now issue. It is not surprising that the Oxford Dictionaries selected "climate emergency'" as the 2019 word of the year. Across the globe people have spent the last 30 years incrementally working to reduce emissions in the hope that we can stop the warming before it becomes dangerous. But after those 30 years we have reached the point where the climate IS clearly dangerous, right now (and worse and worse is in the pipeline if current trends are allowed to continue). The climate movement needs to rediscover the climate issue afresh, as it actually is now (and not as we have became habituated to thinking about it over past decades). Let's work through the logic given the situation we are in, at the start of 2020. The world is dangerously too hot now. Because of current climate change impacts, much of the doubt about the reality of climate change is evaporating. More and more people are beginning (very reasonably) to demand that governments take action to protect them –immediately. Two scenarios could unfold from here. With fires, droughts, heatwaves on land and in the seas, storms, floods etc. battering people and ecosystems, the cost of coping with impacts and recovering and taking adaptive action to lessen the impacts is mounting so rapidly that it would be very easy for societies to switch most of their 'climate' expenditures into dealing with here-and-now impacts. What might this world start to look like? Water shortages will be dealt with principally by investing in desal plants. Forests and woodlands will be too dangerous to live near and they will be mercilessly control-burned or perhaps even cleared. Agriculture will need to be shifted as much as possible into controlled environments (ie. into vast buildings). Across the globe, anyone too poor to invest in such controlled environments will be abandoned (ie. a large percentage of the rural poor and indigenous people living on country), Sea walls will be built, or deltas and coasts abandoned. Marine and terrestrial natural ecosystems will be abandoned. Borders will be closed and people will close their hearts to the struggling and the dying. Wars and insurrections will become more and common in areas too poor to adapt, and quite possibly beyond, and the culture of global cooperation will die. But remember that this is a world that is 'dealing ' with climate change and investing huge amounts very urgently in the process. Is there a better scenario that we could bring into being instead? What might things look like if enough communities around the world decide to do two big things simultaneously, that is:

What has to be done to achieve the second point? If the earth is dangerously too hot now it means that:

Do we know how to carry out any of these steps? Zero emissions: Over the last 50 years a huge amount of work has been put into developing zero emissions energy technologies and this effort has finally delivered technologies that are cost competitive against fossil fuels. So the main things we need to do now is mobilise the political will to urgently close down emissions generating energy systems (covering the use of coal and gas and oil). We also need to accelerate the development and deployment of zero emissions technologies across all the other sectors of the economy. While we absolutely must adopt zero emissions technology at emergency speed, doing so will result in cleaning up the air in regions that burn a lot of coal. This necessary clean-up process will remove particle pollution that has a net cooling effect (lowering the warming effect of coal burning). So, by itself, going to zero emissions (which we must do) will by itself raise the global temperature, once-off by about half a degree. So something more needs to be done. Full scale CO2 drawdown: The earth can be cooled (eventually) by taking all the excess CO2 out of the air. The lowest cost CO 2 capture and storage technologies depend on photosynthesis-driven biological systems – but these systems cannot be scaled enough to deal with all the CO2 that has to be taken out of the air. So additional physical/chemical methods will need to be developed that are affordable at the necessary scale. We know that full-scale CO2 drawdown could take many decades or even hundreds of years to complete. So the cooling effect of the drawdown strategy will not be strong enough for a long time – meaning that massive damage could be done to human societies and natural ecosystems and biodiversity in the meantime. Direct cooling using solar reflection methods. It is already known that the earth can be cooled back to the pre-industrial level at relatively low direct financial cost using solar reflection methods – and the target temperatures could be reached in just a few years. What is not known is whether this can be done with clear environmental/social net benefit globally (ie. would damaging side effects outweigh the direct benefits?). Clearly solar reflection methods should not be used if the net environmental/social benefit is not positive. But given the staggering social and ecological damage that will be done if temperature relief is not delivered very fast indeed, it seems like it would be highly prudent and ethically compelling to immediately ramp up research and development aimed at creating net beneficial solar reflection methods. What does our new situation mean for action and activism? We need to commit to a maximum protection approach to climate action and therefore be clear about:

We need to bring the urgency of real and timely protection to bear on climate campaigning. We can no longer approach climate campaigning largely via a string of drawn out limited target campaigns. We have to press governments to deliver a climate emergency action package that covers “everything”:

Ideally we would want the national government to take the lead from the start and to mobilise the country around this action program. But for practical purposes the current government is best understood as “the fossil fuel industry in government”. And even if Labor won the next federal election, its culture is currently focused on trade-offs and “doing a bit of everything, good and bad, fairly slowly”. Instead, for our immediate action, we need to look a bit further down the government hierarchy to find the critical next focus for action. Between 2016 and 2019, 83 local councils passed climate emergency declarations in Australia (and over 1000 globally). This process needs to be extended to more councils to build the community base, and extended to cover the adoption of an effective action program. But the big qualitative shift for 2020 needs to be to get a number of state governments to declare a climate emergency and adopt the action program described above. This process focusing on the states and territories began on 16 May 2019 when the ACT Legislative Council declared a climate emergency and the potential was further indicated on 25 September 2019 when the South Australian Legislative Council passed a motion calling for a declaration of a climate emergency. We need to be practical, recognising that the fossil fuel industry has its claws less securely into the body politic in some states and territories more than others. You can see this with the ACT, South Australia and Tasmania. There is also potential in NSW and Victoria. If these two big states could be got over the line then the country would really start to shift. Australia is a hybrid polity – part democracy, part monetocracy. To shift Victoria and NSW we will have to convince a large segment of the business community that their wellbeing doesn’t depend on following the interests of the fossil fuel industry, quite the opposite in fact. Building a powerful business alliance against the fossil fuel industry is not a crazy idea. In the 1970s and 80s the mining industry took on the manufacturing industry to press for the elimination of import tariffs. The manufacturing industry was the Goliath with 25% of the business dollars in the economy and the mining industry was the David controlling only about 5% of the business dollars. But the mining industry was eventually able to build an alliance that controlled more than 25% of the dollars in the economy and the alliance together with some skilful strategising rolled the manufacturers and got the tariff change they wanted. The fossil fuel industry in Australia is still a minority economic force controlling less than 10% of the business dollars. But the rest of the economy is not yet fully aware that its interests do not lie with the fossil fuel industry. A campaign to get the NSW and Victorian governments on side for a climate emergency program will depend on mobilising both the community and business around a climate emergency action demand.. And doing both these things will depend on getting support across the political spectrum. Already there are signs that the Liberals and Nations are facing very real internal tensions over the climate issue. The climate emergency campaign began in Australia in 2016 and was created by grassroots climate activists. In the 3 years since then the campaign has built momentum globally, culminating in the passage of a climate emergency motion by the European Parliament on 28th November 2019. The challenge for 2020 is for all of us climate activists to do what we can to get the mainstream climate movement to come at the climate issue afresh, acknowledging that the strategies of the last 30 years are past their use-by date. Now that we are living in the early stages of catastrophic climate change, we have to pull off a massive, urgent and improbable climate rescue. That will require new thinking and new action.  By Adrian Whitehead 7 Nov 2019 Summary Every day we delay action to reverse global warming we increase the chance we will deliver and unsurvivable world to our children, the vast majority of people on this planet and what remains of our world’s ecology. Local councils, the closest level of government to our community, have recently led the world on climate action by declaring that we are facing a climate emergency. Local councils can lead the world again by modeling the response needed by higher levels of government if we are to avoid a climate catastrophe. They can do this by entering a full emergency mode and mobilising their available resources to respond to global warming as the number one priority of council. Local councils action cannot stop with declarations alone or even additional council programs. Each declared council needs a fundamental shift in how it operates. CACE has refocused its campaigning towards getting the first councils in the world to enter emergency mode and is looking for councils, individuals, local groups and organisations to support this campaign. In the article below I discuss the original intent behind the emergency declaration campaign, many of the impediments to achieving full emergency mobilisation we have experienced so far, and what emergency mobilisation would look like if taken on by a council. People interested in the emergency mobilisation campaign can contact myself, Adrian Whitehead, at CACE directly via 0403 735 188 or [email protected] Discussion Scientists are now calling climate change an existential threat to humanity. This means humanity faces potential extinction unless we prevent global warming from reaching temperatures of 2 degrees and above. Given that current international agreements are putting us on track for a 3-4 degree temperature rise, we are clearly in trouble. The future we face will include failure of nation states, mass migration, mass starvation, rise of fascism and ultra nationalism, the death of our oceans, wars fought over water and food. This is all before food growing becomes so difficult smaller and smaller groups of survivors fight to the death over the remaining viable areas, with vast areas of the earth becoming uninhabitable for people and the ecosystems that currently live there. People have a hard time visualising these future so I will take a moment and link them to accessible examples in popular culture. After ever increasing impacts of storms, floods, fire, cyclones etc we the first major global wide event may well be a global food shock, where the amount of food produced falls below demand and need. Many countries will implement martial law as they enforce strict rationing, exile foreigners and decide which parts of their own population is fed and consequently which parts are starved. This future that reflects elements of the movies How I Live Now (2013) or Children of Men (2006). Surviving national states will fight over food resources and water, running the risk of a major nuclear exchange if superpowers confront each other directly or through proxies. If a nuclear exchange occurs we will be living out the futures similar to those shown in the BBC drama Threads (1984) or in the worst case, if enough warheads are fired, the nuclear winter shown in The Road (2009). Even if there is no nuclear war, eventually climate impacts break the remaining nation states and billions starve to death, coasts flood and survivors battle it out in futures that will look more like those envisioned in Mad Max 2 (1981) and Mad Max Fury Road (2015) with the addition that most lands inhabited by survivors are being repeatedly smashed by extreme weather events than being peaceful dusty deserts. Global warming of course doesn’t stop there, remaining forests collapse, methane is released from melting permafrost and formly frozen methane hydrates trapped in ocean floors, creating the conditions of hot house earth pushing the surviving ecology and populations to the edge. This again takes us to scenario’s played out in the The Road (2009) where humans fight over the tiny areas were food can still be grown and while most others hunt humans to stay alive. However it seems these futures are yet to be fully grasped by the broader public, including many of the people who can make a difference and help prevent them from becoming our reality. For example, today over 1000 councils have declared a climate emergency in over 20 countries, but no local government (or higher government for that matter) has chosen to respond in a true emergency manner, missing the opportunity to provide the needed leadership and direction to their communities, other local governments and higher levels of government. This lack of emergency action contributes to delaying the date when we actually start to try and save ourselves. CACE, which was involved in starting the global climate emergency declaration campaign is now focusing on getting the first councils to undertake a true emergency response. Our question to you is, does your council have what it takes to save the world? Why going into emergency mode is important When the climate emergency declaration campaign for councils was developed, it was originally conceived of in two parts. The first part was for a council is to undertake an acknowledgement that a climate emergency was occurring and then to commit to starting a climate emergency response. The second part was a seperate and later motion, originally called "the declaration". This represented the moment that that council moved into full emergency mode, where its climate response was its number one priority, and the council put all its discretionary resources into the emergency response. By doing this it would model the action needed by higher levels of government while at the same time educating their communities about both the problem and the solutions and being the actual taking of mitigation and resilience building needed. If we are to reverse global warming and save ourselves, ALL councils will need to be working in emergency mode along with higher levels of government, so the question is not if, but when council will enter this mode. The first council in the would to acknowledge a climate emergency and start down the emergency path was Darebin council in Melbourne Australia, back in December 2016. This was done as the first motion of the new council using the words, “Council recognises that we are in a state of climate emergency that requires urgent action by all levels of government, including by local councils.” (MOVED: Cr. Trent McCarthy SECONDED: Cr. Steph Amir 5 December 2016) This motion fulfilled the first step of our suggested response and signaled to the community that Darebin Council was commitment to start the process of responding to the climate emergency rather than the Council entering a state of emergency action. Now almost 3 years after the initial acknowledgement by Darebin we have over 1000 councils, several countries, schools churches and other institutions acknowledging or “declaring” we are in a climate emergency. Unfortunately, the original differentiation between an acknowledgement and a declaration has to a significant degree been lost, with many councils and countries now only "declaring" climate emergencies in the broadest sense i.e., acknowledging the problem and as at mid October 2019, as far as we know, no council or government has actually gone into a full emergency mode. Why has no council gone into emergency mode? A few reasons. Firstly the campaign was started and driven but a tiny handful of self funded activists who simply lacked the resources to keep the project fully on track as it took off around the globe. This was compounded in the early days because many “non emergency” climate activists treated the council based emergency declaration with skepticism as they failed to understand the potential impact on the global climate response and its role in accelerating real action on global warming. Once we got councils to acknowledge or declare we often found strong resistance from a range of players including global warming skeptic or denier councillors, with more general resistance from council officers, council managers but most importantly the CEO and council executives who were uncomfortable moving out of a business as usual approach for their council. This often resulted in unwillingness or refusal to act with the needed urgency or a lack of willingness even significantly improve the council’s climate response, let alone go into emergency mode. Other councils seemingly embraced the idea but ultimately failed to break out of business as usual modes of operations and thus fail to enter emergency mode. The lack of uptake by council staff also included not promoting climate emergency response as a priority in their communications and or failing to frame their existing or new actions in the emergency frame, or even promoting non emergency framed climate change as an important issue at all. The lack of focus on communicating the climate emergency undermines the emergency campaign and suggests it is not an emergency at all. For example look at the front page of the websites of some of the earlier adopters such as: Darebin (http://darebin.vic.gov.au/), Yarra (https://www.yarracity.vic.gov.au/), Hoboken NJ (https://www.hobokennj.gov/), Montgomergy (https://www.montgomerycountymd.gov/), Los Angles (https://www.lacity.org/), and Bristol (https://www.bristol.gov.uk/), finds no mention of the word “climate” or “climate change”, let alone the “climate emergency” (all viewed 20 October 2019). It is important to note that many of the councils mentioned above had strong motions for emergency action. For example the Bristol motion included a Bristol wide emergency target of “carbon neutral by 2030“, including consumption emissions, called on the national government to provide the resources needed to achieve this, and demanded a report within 6 months that outlined the action the council will take to achieve this (you can see the response by the Bristol Mayor in July 2019 here https://democracy.bristol.gov.uk/documents/s34127/Climate%20Emergency%20-%20The%20Mayors%20Response.pdf). When presented with these strong motions councils have not risen to the challenge and councillors have not been strong enough or diligent enough to force the CEO’s and senior managers to prioritise a climate emergency response. The fourth element that has undermined the campaign has been organisations rebranding their existing suicidal goals and targets as “climate emergency” targets. A stand out is WWF who attached the “climate emergency” brand to their suicidal goal of net zero by 2045 in a UK petition while in Australia still campaigning for net zero by 2050. An example of this in Australia was Greenpeace. Greenpeace Australia chose to utilise the Council focused Climate Emergency Declaration campaigns to further its anti-fossil fuel campaign and in an attempt to build Greenpeace local campaign groups. Their original “climate emergency” petitions included the non climate emergency target of net zero by 2040 and focused almost exclusively on only one of their campaign targets namely fossil fuels. Greenpeace only changed their target to 2030 when pressured by CACE. Even when similar suicidal goals and targets are not branded as climate emergency targets they still undermine the campaign by claiming that 20-30 years to reach net zero is an appropriate response to global warming. This response has been called soft denialism, a term created by climate emergency campaigner Bryony Edwards, and it contributes to the lack of urgency and outcomes we are seeing today. Soft denialism undermines the call for the radical system change needed, implying that incrementalism and long time frames will do the job. We also see these inadequate goals and targets being promoted in the local government space by groups other than Greenpeace. For example Climate Council’s Cities Cities Power Partnership. The Climate Council claims that provides “authoritative, expert advice to the Australian public on climate change and solutions based on the most up-to-date science”. Yet the Climate Council’s Cities Power Partnership requires council partners to only “select 5 key actions from the partnership pledge” within 6 months. The pledge lists 39 possible actions while completely ignoring animal agriculture. The current limited scope and ambition of the Cities Cities Power Partnership is an example of a council focused campaign that undermines CACE’s campaign to get councils to fully mobilised by creating the impression that a 5 key action response is both reasonable and adequate. The fifth reason is that the emergency mobilisation campaigns are still being affected by past and current anti climate emergency campaigns led by groups such as Australian Conservation Foundation, the communication consultancy Common Cause, and Australia Youth Climate Coalition (AYCC) to name a few. The opposition to “climate emergency” campaigning generally was based around an inability to understand and at times an almost dogmatic belief that emergency framed climate communication could not result in positive campaign outcomes. Fortunately the evidence on the ground suggests otherwise with the creation of a global movement that predated the rise of the student strikers and Extinction Rebellion protests and now includes national governments and significant new initiatives being launched at a number of levels (see the Cedamia website for a current list of government and councils that have declared an emergency), and more recently 11,000 global scientists declaring a climate emergency https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-11-06/climate-change-emergency-11000-scientists-sign-petition/11672776) . There also has been a communication guide produced by Jame Morton in response to the anti emergency critique. Jane, a psychologist and climate campaigner, produced a booklet titled “Don’t mention the emergency”, on why “emergency” framed climate communication works and why those opposing it have got it wrong. You can download this guide here for free. More recently, some groups still are opposing “climate emergency” framing, fearing that an emergency response equates to some sort of imposition of totalitarian government or that an emergency response somehow automatically equates to injustice rather than climate justice and global equity. For example you can read the piece by Kelly Albion from AYCC on May 15, 2019 (her article is here). The view that an emergency response automatically leads to injustice is quite delusional as climate justice can and should be incorporated into any and all climate emergency responses. Groups such as Save the Planet and CACE have always done so, for example CACE encourages councils to use their climate emergency response to help the most disadvantaged members of their community by helping reduce energy poverty, reduce food insecurity and improve the quality of houses in terms of thermal comfort etc. An overseas example is the Climate Emergency Institute, established in Canada, which calls for “The climate crisis demands compassion and respect for the basic human rights of the huge populations of the most climate change vulnerable with respect to their health, livelihood and survival.”

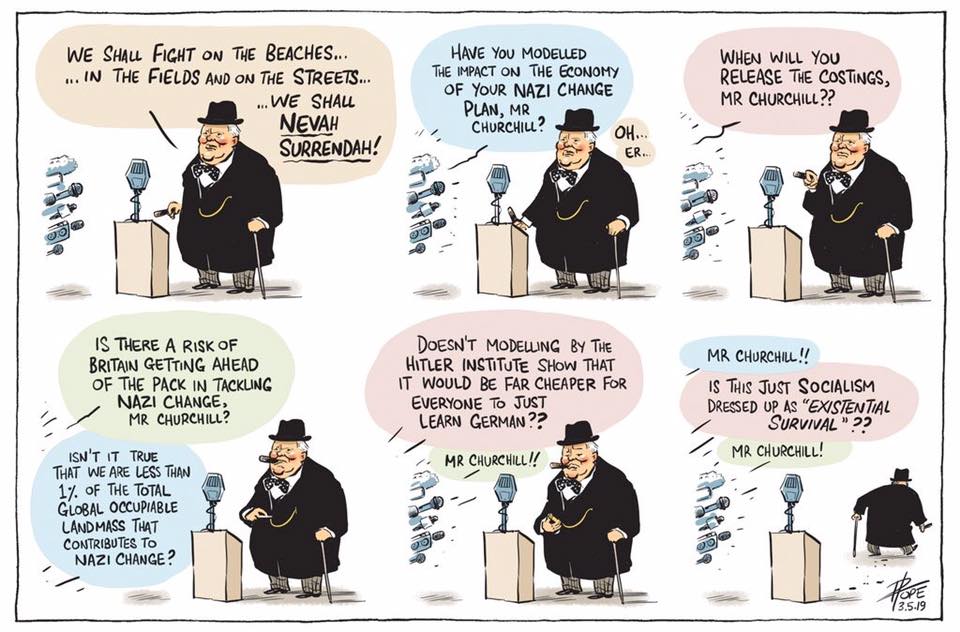

If we want to look for climate injustice, the real climate injustice and crime against humanity being perpetrated is the suicidal goals, inadequate targets, and blanket rejection of most geoengineering options. This includes the presentation of single issues solutions promoted by major eNGO’s including by AYCC,as acceptable responses to global warming when they will not prevent a climate catastrophe and will in fact lead to the death of billions and the loss of most of our ecology. There is some risk of course that the scenarios that Albion talks about may come to pass, and even much worse, but these are much more likely to happen if we delay our emergency response rather than be proactive and start it now. If we fail to reverse global warming before the impacts become too severe, ultra nationalism and isolationism will inevitably arise and the opportunity to achieve major social justice and equity outcomes on a global scale will be reduced or be lost. Why is this a problem? Where to next? Clearly councils failing to take the next step sends the wrong message to community and higher levels of government that inaction or mediocre action is the acceptable response to the climate emergency. Consequently CACE is refocusing our campaign to get the first councils in the world to go into emergency mode and are looking for councils, community groups and individuals to help us start these campaigns. Ideally your council has already made some sort of climate emergency declaration but this does not need to be the case. If they have made a climate emergency declaration you can now focus on an emergency mobilisation campaign, if they haven’t you can try for both. CACE describes lots of ideas for community campaigning to put pressure on your council on our website under the section “Building a Campaign” (https://www.caceonline.org/build-a-campaign.html). The gold standard for community engagement is to go house by house in your council area discuss your council going into emergency mode, including why we need to this and what this would mean for council operations. You then ask the household if they support such action. In this way you can eventually report to council your level of community support, street by street. This method was used by the Lock the Gate campaign to declare council area and towns “frack free”. See the town of Bolloloola in the NT declare their town frack free (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XoJd09dnoXM). CACE is producing a template for a leaflet soon to help your communication with your community. What is the criteria for a council to be in full emergency mode If you are interested in starting a climate emergency mobilisation campaign in your community you will need to develop an understanding of what it means. In short we define full emergency mode as: - the climate emergency response (mitigation, resilience, education and advocacy) is the number one priority of council - staff training has been undertaken for all staff, including managers and the CEO, focused on the climate emergency and the role of council in the areas of mitigation, resilience, education and advocacy - the council has undergone a whole of council review of existing policies and practices to identify where climate emergency outcomes could be achieved in the area of mitigation, resilience, education and advocacy, through modified business practices, modified policies, new programs or new policies, including reviewing the councils fund management and procurement policies - the council has done an emergency budgeting exercise and has identified all available discretionary funds that can be directed to a climate emergency response and has committed these funds - a new climate emergency policy should be developed incorporating the areas of mitigation, resilience, education and advocacy. The new policy should be focused on achieving multiple benefits beyond just a global warming response such as supporting the most disadvantaged members of the community, and include all emissions sources including consumption - the climate emergency response should feature as the lead issue in all general council communications including the home page of the website and any community newsletters. In an emergency, every opportunity is taken to communicate the emergency to the community - the council is mobilising its community to support their action and work with council to achieve net negative emissions by 2030 or earlier including putting pressure on higher levels of government. - a community wide planning process has been undertaken for how the council can achieve net negative emissions, including consumption emissions, by 2030 or earlier within the broader community, including the development of key target areas, key partnerships and budget requirements. We describe this in significant detail on the CACE website including the steps a council can take to enter an emergency mode and what this looks like on our pages: - Motions to Declare a Climate Emergency (https://www.caceonline.org/motions-to-declare-a-climate-emergency.html), - Entering Emergency Mode (https://www.caceonline.org/entering-emergency-mode.html), - Your Climate Emergency Plan (https://www.caceonline.org/your-climate-emergency-plan.html). CACE is keen to help If you are wanting to start a climate emergency campaign probably the best thing is talk the ideas with a CACE campaigner. CACE is happy to support you campaign by helping you get across the basic ideas, helping you develop a campaign plan, providing a speaker for a public event or in any other way you think might help. Contact CACE director Adrian Whitehead directly via mobile 0403 735 188 or email [email protected]. Have there been positive outcomes from the emergency declaration campaign? Absolutely! The emergency framing of global warming has refocused attention on the inadequate action our state and federal governments and the dire threat of current and future global warming. It has added a sense of urgency to our actions and helped flush out climate skeptics and deniers as well as those putting the short term interests of corporations over the people and ecology of this planet. In many parts of the world climate emergency acknowledgements and declaration have lead to new and improved climate programs that would not have occurred without the movement. Many communities have used climate emergency campaign to conduct large scale community awareness campaigns in communities where there has never before seen a climate campaign of any description. Public halls have been filled to overflowing, petitions have been collected and doors knocked. For example despite losing their emergency motion at council, the Knox climate emergency campaign group, was this first on the ground climate campaign in their area, making face to face contact with over 1% of the population of their council over just a couple of months. Combined with the increasingly strong protest movements lead by the Climate Student Strikers and Extinction Rebellion, the emergency declaration campaign provides a pathway to eventually get state and federal governments on side. Countering the top councillor arguments against declaring and mobilising in the climate emergency30/8/2019 Bryony Edwards R If a councillor is not a hard climate denier but argues against the council acknowledging/declaring and mobilising on the climate emergency, their arguments are probably as follows:

Argument #1: If Council declares a climate emergency, it will have to follow up with emergency action and through the acknowledgment could become financially liable. Response: Without an appropriate climate emergency declaration and planning, Council is more likely to be left legally exposed because climate risk management will not be prioritised. There are often two components to this general concern: firstly, that a climate emergency acknowledgement would mean Council would need to follow up with action, and secondly, the potential for Council liability if it didn't follow up the acknowledgement with commensurate action. The obvious response to the first part of this concern is: Yes, of course Council has to follow up with commensurate action, which means prioritising climate risks. With regard to liability, the thinking goes that if the severity of climate risk is acknowledged and Council does not adequately prepared for the risks, (eg, for unprecedented flooding) if the risk is realised, the council could be liable for damages. However, 'ignorance' of the severity of climate risk is no longer a legal defence. It is Council's business to be aware a full range of climate threats, as relate to the physical landscape and infrastructure, planning and delivery of basic council services, and general wellbeing of the community. This is made very clear in this 2016 Australian legal assessment of 'Directors' climate liability exposure increasing exponentially'. Climate science and mainstream assessment of resulting risks is too established across most sectors for 'ignorance' to be seen as anything but 'negligence'. Council's exposure to future litigation around inaction on climate change only strengthens the argument that Council should acknowledge/declare climate emergency to ensure priority is given to climate risk management (via the declaration and climate emergency plan, prioritised in Council's strategic plan) Without the acknowledgement/declaration, climate risk management will not be prioritised and Council will be left exposed. Furthermore, any council that is considering a climate emergency declaration should have been informed to a significant degree by community activists, staff or other councillors, and hence in any future litigation, would not be able to claim ignorance. For example, in 2017-18, CACE emailed every Australia with an email address a letter outlining the climate emergency and what council could do in response. We could see a future time when today's community activists are presenting in court their efforts to get emergency action by local council staff and councillors. It is true that Council liability would be more likely to occur from failure to build resilience in the community to mitigate impacts, as opposed to failure to reduce emissions; however, it is a happy coincidence that resilience building and emissions reduction often go hand in hand: creating biochar from organic waste makes soil more resilient to drought while also reducing emissions; growing food locally builds community resilience and reduces emissions; making a grid more resilient means it is likely to rely more on renewables and storage, so will also have lower emissions etc. This CACE blog provides more detail on legal and cost implications for councils that bury their head in the sand. Argument #2: Council is already doing everything it can regarding climate. Response: Is the council telling the community we are in a climate emergency? What proportion of discretionary spending went on climate related lines in the current budget? Is organic waste diverted from landfill? Does Council prioritise climate initiatives in their strategic plan? What climate related measures is the CEO held to account on? If Council is actually doing all it can then why not acknowledge/declare a climate emergency? Emergency thinking and acting is a paradigm shift from business as usual and the same goes for climate emergency thinking and acting. A council doing everything they can assesses everything they do with a climate emergency lens: -basic operations are assessed and revised with regard to the emissions reduction and resilience building (see #3 below) -discretionary spending is directed towards the climate emergency -the CEO is assessed primarily against measures from the climate emergency plan -the urgency is reflected in Council's strategic plan. Argument #3: Our community want us to stick to basic services. Response: Basic services are all levers for climate emergency action, both local resilience building and reducing emissions. Even if limiting the council portfolio to its bare minimum (which varies by country and council type), this does not prevent council from putting a climate emergency lens across their basic services: rates, roads, rubbish, buildings, power purchases, community services, and planning and implementing best practice. Where the funds are not available the lobbying the state and federal government comes into play. CACE is building a clearinghouse of ideas on its Post Declaration page. Argument #4: Climate emergency is the business of state and federal governments, not councils. Response: Are state and federal governments currently leading a climate emergency response? Global emissions are still going up and we've set off numerous positive feedback loops/reached tipping points. Yes, ultimately state and federal government are in control of the big economic regulatory levers but getting state and federal governments to the climate emergency is, to understate the issue, an uphill push. Councils are the ones to get the ball rolling. Councils also have broad portfolios with many levers for reducing and drawing down emissions and getting the community on board. When a central government declares a climate emergency, they will look to local governments and ask 'Right, now what are you going to do?'. Councils need to start preparing now. Ask the councillor: if not the international council campaign, how else do you see the planet being saved? The alternative is giving up. Argument #5: A climate emergency declaration would be 'virtue signalling'. Response: A climate emergency declaration is not virtue signalling if Council is prepared to follow up the words with real action. Virtue signalling involves expressing opinions or sentiments intended to demonstrate one's moral correctness on a particular issue. If a council is prepared to take strong action or even mobilise, this demonstrates that the declaration is more than an empty gesture. Image Source: InDaily As of 1 July 2019, 719 councils across 16 countries have declared a climate emergency. With the first to declare in December 2016, the number of councils that has declared has doubled in the past four months, as made available in the global list managed by CEDAMIA.

Moreover the New York City has declared and a number of nations have joined including Canada. This upward momentum to central governments was a goal when the council climate emergency campaign was first developed. The campaign has introduced the emergency frame to campaigners, policymakers and the public around the world, changing the tweaked business-as-usual approach to which many had become resigned. The council campaign has gone hand in hand and been boosted by Extinction Rebellion and School Strikes. While advocacy and education are central to the council campaign (up, down, sideways and inwards) the nuts and bolts solutions package is also essential. How do councils best shift to reduced or zero emissions and drawdown, while building community resilience across their portfolios? If councils declare a climate emergency and but don't mobilise to adopt the emergency frame across their portfolios, we have lost because all stakeholders will become resigned to it being just too hard - back to the tweaked business as usual approach. Councils have to walk the talk. Change doesn't come easy - that's why consultants make millions selling change management to corporation. This is the type of intervention each council needs to undergo so that councillors, the CEO and staff are all on the same climate emergency page. CACE is working on a training package for councils. If your council has declared, hold them to account. CACE is working on some of the nuts and bolts for once councils have declared. Ultimately we would like to work these into guides to make it simpler for declared councils. Any specialist help is appreciated. Bryony Edwards 5 May 2019 (Updated on 10 May 2019) As climate emergency talking and thinking shifts further towards climate emergency action, it is imperative that ‘climate emergency’ is not co-opted to mean something ‘convenient’ or ‘pragmatic’ (ie. weak goals and slow action). Climate emergency has to stand for safe climate principles for restoring a safe climate. So what should climate emergency emissions targets look like? This blog attempts to draw a line in the sand, proposing how to set targets for both central governments and councils from an NGO or campaigning perspective. Where are we today in the climate emergency campaign? In the space of 5 months, the phrase climate emergency has become household. Several months ago, the hashtag #climateemergency appeared in two tweets a week from a handful of the usual suspects. A snap count now shows 80 odd tweets in the past 30 minutes, including from mainstream voices. For the last few weeks, 1000s with Extinction Rebellion are blocking central streets and bridges in London, demanding that their government implement a climate emergency response. Just a few weeks ago, The Australia Institute released findings from a nationwide survey that the majority of Australians believe we face a climate emergency and want to see a ‘climate emergency’ response including the type of ‘mobilisation of resources undertaken in WWII’. Use of this language alone is a paradigm shift. As of today, the phrase, climate emergency’ is used by:

What is the original intended meaning of 'climate emergency'? Among different campaigners, early uses of the term 'climate emergency' varied slightly but captured the the intention of safe climate restoration at emergency speed. Dedicated campaigners introduced 'emergency' to communicate the urgency and systems change needed, which was in stark contrast to the sluggish aspirations of mainstream environmental organisations and 'good' politicians. The thinking for what climate emergency in action looked like was based on work of organisations like Centre for Alternative Technology (UK) and Beyond Zero Emissions, (Aust) in the mid 2000s and their urgent sector wide transition plans. Centre for Alternative was using the term 'Climate Emergency' coupled with an emergency response. The transition timeframes proposed for the solutions packages were as short as 10 years. From a Australian perspective, grass-roots climate campaigners started using the term at least as far back as 2008 (eg. in Climate Code Red) to represent what was needed to restore a safe climate. The expression was used 26 times in this linked article from 2013. 'Climate Emergency' was formalised in May 2016 with the Australian ‘Climate Emergency Declaration’. In the US, the term appeared at least as early as 2011. It was probably The Climate Mobilization that popularised the term. No doubt there were other early uses of the term so apologies if these uses have not been captured. More detail on the history of climate emergency is available here. Maximum protection = maximum effort at maximum scale and speed While today there is an ever-loosening use of the term climate emergency, people using the term need to understand that

Because we have an extremely dangerous climate now and switching to a zero carbon society still leaves us with today’s carbon in the atmosphere plus what will be emitted between now and the day we achieve the zero-carbon goal, zero emissions is not a safe end target. Philip Sutton, Co-Author of 'Climate Code Red' has stated that 'We need a step before setting the goal of restoring a safe climate. Restoring a safe climate is a means to an end – providing protection so the first question is who and what are we trying to protect? Why do we want to protect them? For ethical reasons or because they are a means to protecting something else? And how secure do we want that protection to be?' Philip's view and the only ethical view, is that we should aim to protect all people, species and civilisation globally and we should aim to protect the climate vulnerable. He calls this 'maximum protection'. To provide maximum protection we need to do two things:

If you agree with the maximum protection principle, the only course of action is to bring other organisations and governments on board. The same goes for 1.5C goals because maximum effort, scale and speed will also be required.* As such, we need to go to negative emissions to restore safe (pre-industrial) greenhouse gas concentrations (safe at about 280-300ppm) and restore a safe climate. Getting to negative emissions ASAP means:

While these 3 demands are a tall order and extremely ‘inconvenient’, there’s a very high chance anything less is giving up on a liveable planet and our futures. If we are not very clear with our expectations (targets), they will not be met:

Is everyone talking climate emergency using the safe climate restoration frame? No. For example, there are councils passing climate emergency declarations that are aiming for net zero by 2050; this includes large councils such as the London Assembly and Vancouver. After declaring, London quickly went on to approve another runway at Gatwick. Although the UK made a ‘resolution’ for a climate emergency, Labour and Tory Councillors in Cumbria went on to back a new coal mine. The UK’s Committee on Climate Change (the CCC), an independent, statutory body established under the Climate Change Act 2008, has recommended just ‘zero by 2050’ for the UK’s emergency response. The CCC is similar to Australia’s Climate Council, which recommends the same target for Australia. It shouldn’t be surprising that soft targets are defeatist. Soft targets set us up to fail. What is the role of targets? Governments usually set targets before the full suite actions for how they will be achieved is known. As such, they tend to set targets for complex work far into the future. But decades-out targets can be easily ignored because any one government can’t be easily held to account. A target ideally works as a slogan of 3 to 5 words, and needs to communicate ‘what we need to do and how fast should it be done’. The target can also include more detail, such as interim or contributing targets, which can hold any single government to account. Given the scope of work for a climate emergency response, once adopted, a climate emergency target should drive policy development, governance and performance measurement across all of government’s work. The target implicitly communicates the degree of priority the work will need, which in this case is maximum priority. There are good arguments for not providing a target deadline in case it is too ambitious and stakeholders expect failure, but this is outweighed by the benefits of having a timeframe (or the cons of not having one). And with the right governance, more will be achieved with an ambitious target than with a less ambitious one. A recent example of a target at work is Oxfordshire Council (UK). At the time of writing this, Oxfordshire Council is trying to weaken the target they set with their climate emergency declaration (zero by 2030). The council is worried they won’t meet the target. Perhaps not but having such an ambitious target means the council will have to go above and beyond to try to meet it. When setting goals for safe climate restoration, it is implicit that these goals will require:

Because we have to demand the action needed first then it’s important we get the targets right. Our governments will latch onto the easiest around and then may fall short of them anyway. Governments will look for a path requiring the least amount of effort, whereas we need a herculean effort. A brief history of climate target setting We are currently grappling with a very climate-confused public not only due to years of misinformation from hard climate deniers, but also misinformation from the soft climate deniers, generally the large environmental organisations, who are supposedly representing a safe climate but present weak targets for governments. People trust in these environmental organisations so they trust the targets of ‘zero by 2050’ that they promote. Hence the general confusion around what a safe target is. Ask a random person whether zero by 2050 is safe climate policy and they’ll probably say yes. If we are too hot now, how can net zero by 2050 mitigate the impacts we are experiencing today, let alone save us? Why have environmental organisations set weak targets? Environmental organisations set weak goals because they wanted to be taken seriously by government - they want a seat at the table, but in addition they have:

The environmental organisations should have been asking themselves, ‘how do we get the public on board to drive an effective campaign with government?’, not ‘what will government accept?’ or 'What will get us a seat at the table?'. In private conversations, staff from these environmental organisations confide that the goals they are setting ‘couldn’t save us’ but they ‘don’t want to frighten people away’. These eNGOs have effectively given up and have created havoc in their wake. This environmental organisation campaigning logic was a bit like trying encourage locals to stay and fight an oncoming bushfire by lying that the fire is 200km away, when in fact the fire is already throwing embers and all roads out are closed. Which would you imagine to be more effective at motivating to stay and fight the fire? The eNGOs chose the 200km option. Jane Morton’s booklet, ‘Don’t Mention the Emergency?’ examines this campaigning dissonance in detail. If the environmental organisations had been campaigning on safe climate goals for the past few decades, we would be in a very different place today with regard to public understanding and what they demanded from government. Yes, the hard deniers would still be around but we wouldn’t be dealing with such a high degree of public confusion on what we need to do. What are the risks if we couple climate emergency with suicidal targets now? Just in the past week, two large environmental organisations have finally woken up to the fact that ‘fear’ is in fact a necessary tool for climate campaigning and have declared a climate emergency. These same eNGOs had refused to use ‘fear’ in climate campaigning for years. ‘Climate emergency’ as a term was officially blacklisted by professionals campaigning for climate action. As with the past so with the future. If the organisations with the biggest profiles and deepest pockets couple the ‘climate emergency’ headline with soft targets, nothing will have changed other than the word ‘emergency’ and the broader public will believe they are in good hands with the lobbying on their behalf. Environmental organisations’ inability to shift into emergency mode has just been confirmed by WWF. WWF has jumped on the ‘emergency’ bandwagon with their declaration last week but only moved their ‘net zero’ target forward five years from 2050 to 2045. And these decades-out targets are what governments will adopt, regardless of what is actually possibly under a mobilisation response with technical breakthroughs that mobilising economies can drive ahead of the deadline. Imagine if in 1970, we set 30 year deadlines based on the technology available at the time! Most governments will do all they can to compromise emissions targets. Climate campaigners supposedly campaigning for a safe climate shouldn't do it for them. Reject suicidal targets from any group speaking on behalf of the planet and promote safe climate targets! Climate-emergency target setting For maximum protection, we need to set targets based on what can be achieved under ideal circumstances (ie emergency action), not business as usual or a supposedly pragmatic view on what our current political landscape can deliver. High level targets for central governments What we need to capture in a high level target is three main components:

But how to turn this 3-part target a slogan of 5 words or less? These could include:

If implemented globally it could be ‘A cooler planet by 2025’ or ‘a safe climate by 2030’ Targets for Councils A council target is more complicated because many councils lack regulatory and economic levers to achieve net zero or net negative emissions. Councils should acknowledge:

In addition, the council can state what they will do or achieve across each sector that is within their control. In the declaration, these targets could be captured as, for example:

Last word It is amazing what can be accomplished in emergency mode (Eg UK in WWII) when government realigns to achieve something ambitious, when the public is properly informed, when vested interests are forced to stand down. If this is our last ditch effort at saving the planet, why would we comprise safe climate principles before we’ve even sat at the government negotiating table? Compromising on safe climate principles is how we got here in the first place. *In the CACE Goals and Targets Fact Sheet available in the Toolbox we discuss how Maximum Effort would be required to meet goals such as maximum protection, minimum protection, and acceptable risk |

AuthorsBloggers on this page include Adrian Whitehead, Bryony Edwards, Philip Sutton. Archives

July 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed